Organization Horsepower was written based on my experiences in life and business. One of those experiences was the time I spent as a crew member on race team. In the book, I tried to keep things simple by concentrating on how a race team functioned in relation to performance. How successful I was at that endeavor I will leave to you, the reader. However, today I feel a tinge of regret that I did not more fully explore the people who served with in those roles. In all cases, those people defined the roles they played on the team and they served in those roles because of who they are, not because it was the role we had to fill.

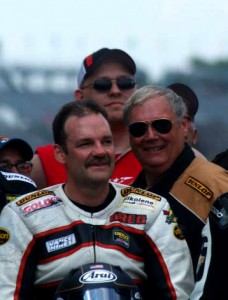

One of those people, is Bruce Blake, Crew Chief for the Greg Hutcheson Racing team.

The reason why I feel compelled to talk specifically about Bruce is because he passed away the morning of July 16th. Much of what I know about motorcycle racing at the professional level I learned from Bruce, and to cater to cliché, Bruce had forgotten more about racing than I will ever know. In this article, I will analyze the role that Bruce played in the content of the book and try my best to honor his contribution.

Before we look, at the role of Crew Chief, it’s helpful to understand the context of that role by understanding the overall structure or Organizational Design of the race team. The following excerpt is from chapter 8, “The Crew”:

Organizational Design of a Race Crew

Organizational design (OD) on a race team is purposeful and lean and is comprised of specialists who are well aware of their contribution to the cause. Much like in business, a smaller capital investment means that each crew member must play more, less-specialized roles. However, as capitalization grows, the race team can scale based on its strengths. The overall structure of a race team remains flat. Everyone has a job to do, everyone knows why it’s important, and everyone is accountable. Most race crews are made of up of these four identities: team owner, crew chief, team manager, and specialists.

Bruce was an Engineer by trade, a motorcyclist by passion. He approached motorcycle racing from the perspective he knew best, with precision and a scientific understanding of the interplay of the mechanics of the rider and machine.

Of the many stories Bruce had to tell, it was never clear to me how involved he was with racing before his son Justin Blake got involved with racing, first in motocross, and then adding road racing. Justin was the Bo Jackson of motorcycle racing, riding at the professional level in both motocross and road racing simultaneously. In addition to role as Father, this is where Bruce first assumed mantle of crew chief.

Subsequent to Justin’s racing career, Bruce ran a successful racing focused shop with particular specialty in suspension. However, being the crew chief in a family-based race team meant at one time or another he played all the roles on the team, some at the same time.

This juxtaposition makes me wonder how much of our traditional corporate organizational design is influenced by traditional western family roles. Regardless, Bruce had a unique set of life experiences, combined with a perspective that made him our ideal Crew Chief. Once again, the following excerpt is from chapter 8, “The Crew”:

Crew Chief

Like the rider, the crew chief fills several roles in the structure of the race team. Before the race, the crew chief is a trainer and a coach, making sure the crew can execute exactly as they need to come race day. The chief makes sure the crew has all the parts and tools they need to their jobs. The chief works with the rider during development, interpreting for the crew what the rider feels he needs from the machine. The chief also acts as an advisor for the rider by providing the data needed to increase performance.

On race day, the crew chief is the head coach, directing and coordinating the efforts of the crew and the rider to maximum performance. The crew chief is the business equivalent of the COO (Chief Operating Officer), responsible for the execution of all the organization’s core competencies.

…

When a rider and crew chief work well together, they tend to stay together, sometimes even switching teams together as a package deal. It speaks to the complex but symbiotic relationship that can develop between the visionary and the operational aspects of a high-performing team.

When it works, you tend to want to leave it alone. This type of symbiotic relationship is also often seen at the upper echelons of corporations, with really great entrepreneurial officers who bring trusted operations leadership with them from company to company.

Bruce was meticulous in in his planning, he had checklists for what tools needed to be on pit lane, and had a special tool box to get them there. He ran drills with us on who stood where and how not to get in each others way. He knew that if we knew exactly what we were supposed to do, he could concentrate on the rider, what the rider wanted from the machine, and what adjustments needed to made for changing conditions.

Greg Hutcheson, the rider, is also an engineer by trade, and the relationship they were able to forge was able to reach that symbiotic level. They shared a common lexicon, and common understanding of speed and performance, but in a way that they both continued to learn from one another.

As for me, I learned a couple different jobs on the team, learned a whole lot about the mechanics of motorcycles, and even got to spend a couple race weekends where I was the rider and Bruce was my crew chief of sorts. Perhaps more important, I learned what it took and what it meant to lead an organization’s operational aspects. A lesson that I will today, and will forever aspire to embody.

In Memory of Bruce D. Blake, 19??-2016